It’s an exciting process to get certified as a hypnotherapist. This unique modality offers the opportunity to make a dramatic impact on individuals eager to overcome many of life’s day-to-day challenges.

It’s an exciting process to get certified as a hypnotherapist. This unique modality offers the opportunity to make a dramatic impact on individuals eager to overcome many of life’s day-to-day challenges.

The bad news is that becoming a new hypnotherapist offers two significant challenges. The first hurdle is becoming a proficient practitioner. There is so much more to being a great hypnotherapist than a few scripts and relaxing music. It takes time to develop your style, find your voice, and to craft effective sessions.

The other challenge is becoming self-employed. It’s not as though you can get a job at the local hypnotherapy clinic. Most small businesses fail and to make matters worse you are attempting to sell services in a profession that is widely mocked, misunderstood and marginalized.

The good news is that if you set-up a modern practice with high-end audio and a google-friendly web presence, you’ll always be busy offering eager clients consistently positive results.

Also, since most states, my state of Massachusetts included, have no regulations for hypnotherapy anyone can take a week-end seminar, get a certificate and go into business. So, it doesn’t take much to stand out from the competition.

This virtual 6-class mentoring program is for certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. This program offers a multileveled approach including a dynamic client office experience, live digital recording of client sessions, MP3 file sharing, cable TV show production with search engine optimization, blogging and social media distribution.

This virtual 6-class mentoring program is for certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. This program offers a multileveled approach including a dynamic client office experience, live digital recording of client sessions, MP3 file sharing, cable TV show production with search engine optimization, blogging and social media distribution.

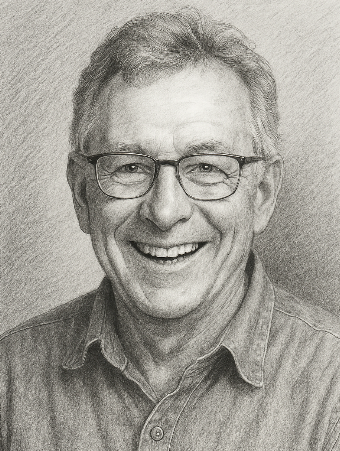

Hypnotherapist Paul Gustafson RN CH offers a 6-class mentoring program for new certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. Paul incorporates high-end audio and video along with creatively effective sessions which offers eager clients consistently positive results. [more]

Hypnotherapist Paul Gustafson RN CH offers a 6-class mentoring program for new certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. Paul incorporates high-end audio and video along with creatively effective sessions which offers eager clients consistently positive results. [more]

Paul’s multilevel approach includes a dynamic client office experience, digital recording of client sessions, MP3 file sharing, cable TV show production with search engine optimization, blogging and social media distribution. [contact]

Hypnotherapist Paul Gustafson RN CH offers a 6-class mentoring program for new certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. Paul incorporates high-end audio and video along with creatively effective sessions which offers eager clients consistently positive results. [more]

Hypnotherapist Paul Gustafson RN CH offers a 6-class mentoring program for new certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. Paul incorporates high-end audio and video along with creatively effective sessions which offers eager clients consistently positive results. [more]

Paul’s multilevel approach includes a dynamic client office experience, digital recording of client sessions, MP3 file sharing, cable TV show production with search engine optimization, blogging and social media distribution. [contact]

Hypnotherapy — or hypnosis — is a type of nonstandard or “complementary and alternative medicine” treatment that uses guided relaxation, intense concentration, and focused attention to achieve a heightened state of awareness that is sometimes called a trance.

Hypnotherapy — or hypnosis — is a type of nonstandard or “complementary and alternative medicine” treatment that uses guided relaxation, intense concentration, and focused attention to achieve a heightened state of awareness that is sometimes called a trance.

The person’s attention is so focused while in this state that anything going on around the person is temporarily blocked out or ignored. In this naturally occurring state, a person may focus their attention — with the help of a trained therapist — on specific thoughts or tasks.

How Does It Work?

Hypnotherapy is usually considered an aid to certain forms of psychotherapy (counseling), rather than a treatment in itself. It can sometimes help with psychotherapy because the hypnotic state allows people to explore painful thoughts, feelings, and memories they might have hidden from their conscious minds. In addition, hypnosis enables people to perceive some things differently, such as blocking an awareness of pain. Hypnotherapy can be used in two ways, as suggestion therapy or for patient psychoanalysis.

Suggestion therapy: The hypnotic state makes the person better able to respond to suggestions. Therefore, hypnotherapy can help some people change certain behaviors, such as to stopping smoking or nail-biting. It can also help people change perceptions and sensations, and is particularly useful in treating certain kinds of pain.

Analysis: This approach uses the relaxed state to explore possible unconscious factors that may be related to a psychological conflict such as a traumatic past event that a person has hidden in their unconscious memory. Once the trauma is revealed, it can be addressed in psychotherapy. However, hypnosis is nowadays not considered a “mainstream” part of psychoanalytic psychotherapies.

What Are the Benefits?

The hypnotic state allows a person to be more open to discussion and suggestion. It can improve the success of other treatments for many conditions, including:

Phobias, fears, and anxiety

Some sleep disorders

Stress

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Grief and loss

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

It also might be used to help with pain control and to overcome habits, such as smoking or overeating. It also might be helpful for people whose symptoms are severe or who need crisis management.

What Are the Drawbacks?

Hypnotherapy would not be appropriate for a person who has psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, or for someone who is using drugs or alcohol. It should be used for controlling some forms of pain only after a doctor has evaluated the person for any physical disorder that might require medical or surgical treatment.

Hypnosis is also not considered a standard or mainstream treatment for major psychiatric disorders like depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or serious personality disorders. It is not a substitute for more established forms of psychotherapy or medication treatment used for these types of conditions.

Some therapists use hypnotherapy to recover possible repressed memories they believe are linked to the person’s psychological problems. However, hypnosis also poses a risk of creating false memories — usually as a result of unintended suggestions by the therapist. For this reason, the use of hypnosis for certain mental disorders, such as dissociative disorders, remains controversial.

Is It Dangerous?

Hypnotherapy is not a dangerous procedure. It is not mind control or brainwashing. A therapist cannot make a person do something embarrassing or that the person doesn’t want to do. The greatest risk, as discussed above, is that false memories can be created. It is also not a recognized standard alternative to other established treatments for major psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depression.

Who Performs Hypnotherapy?

Hypnotherapy is performed by a licensed or certified mental health professional who is specially trained in this technique.

WebMD Medical Reference

Most clients are pursuing hypnotherapy for the first time. They are not only new to hypnosis but have no experience with meditation, guided imagery or progressive relaxation. Most want to overcome long-term personal challenges with weight, stress, addiction or fear.

Most clients are pursuing hypnotherapy for the first time. They are not only new to hypnosis but have no experience with meditation, guided imagery or progressive relaxation. Most want to overcome long-term personal challenges with weight, stress, addiction or fear.

There is a common thread of frustration when clients discuss their situations: dieters fail; medications, at best, are just symptom management; and traditional talk therapy is often described as a constant reminder of the problem with no sustainable solutions. New clients may not know much about hypnotherapy but they have a really good idea of what hasn’t work so far.

Important components to success with hypnotherapy involve comfort and trust. If new clients are comfortable with the practitioner, the surroundings and trust that this individual is acting in their best interest, then chances of a positive client experience are greatly enhanced.

My sessions run about 20 minutes. With clients wearing Bose noise-cancelling headphones, my voice is evenly mixed with soothing music and nature sounds delivered through a high-end audio system. It’s during this relaxed, receptive level of thought, where positive supportive suggestions and imagery can become quickly rooted.

The initial advantage of hypnotherapy over other modalities is that it feels really good. Overwhelmed, stressed-out clients typically experience deeper relaxation than they’ve experienced in a long time, on the initial visit.

Another even more significant advantage is the meditative effect. People who routinely meditate are more relaxed, focused and mindfully aware of what is important to them. They don’t act impulsively, they make better choices, and they are happier, healthier and live longer. Think of hypnotherapy as goal-oriented meditation.

In fact, most clients experience unexpected freedom, clarity and relief in areas unrelated to what they came to fix because of this meditative effect. In general, they are more relaxed and confident which usually translates into better communication with others and a sense of feeling more in control. Clients also typically report increased depth and quality sleep; awakening more refreshed and energized.

In fact, most clients experience unexpected freedom, clarity and relief in areas unrelated to what they came to fix because of this meditative effect. In general, they are more relaxed and confident which usually translates into better communication with others and a sense of feeling more in control. Clients also typically report increased depth and quality sleep; awakening more refreshed and energized.

My clients get an MP3 recording of each session for home reinforcement which they can access with their phone. By listening to sessions on a daily basis this relaxing, mindful perspective becomes their new baseline, making it much easier to succeed with their goals. [contact]

by: Paul Gustafson RN CH

It’s an exciting process to get certified as a hypnotherapist. This unique modality offers the opportunity to make a dramatic impact on individuals eager to overcome many of life’s day-to-day challenges.

It’s an exciting process to get certified as a hypnotherapist. This unique modality offers the opportunity to make a dramatic impact on individuals eager to overcome many of life’s day-to-day challenges.

This virtual 6-class mentoring program is for certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. This program offers a multileveled approach including a dynamic client office experience, live digital recording of client sessions, MP3 file sharing, cable TV show production with search engine optimization, blogging and social media distribution.

This virtual 6-class mentoring program is for certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. This program offers a multileveled approach including a dynamic client office experience, live digital recording of client sessions, MP3 file sharing, cable TV show production with search engine optimization, blogging and social media distribution. Hypnotherapist Paul Gustafson RN CH offers a 6-class mentoring program for new certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. Paul incorporates high-end audio and video along with creatively effective sessions which offers eager clients consistently positive results. [more]

Hypnotherapist Paul Gustafson RN CH offers a 6-class mentoring program for new certified hypnotherapists interested in taking the fast track to professional success. Paul incorporates high-end audio and video along with creatively effective sessions which offers eager clients consistently positive results. [more]

Hypnotherapy — or hypnosis — is a type of nonstandard or “complementary and alternative medicine” treatment that uses guided relaxation, intense concentration, and focused attention to achieve a heightened state of awareness that is sometimes called a trance.

Hypnotherapy — or hypnosis — is a type of nonstandard or “complementary and alternative medicine” treatment that uses guided relaxation, intense concentration, and focused attention to achieve a heightened state of awareness that is sometimes called a trance.

Most clients are pursuing hypnotherapy for the first time. They are not only new to hypnosis but have no experience with meditation, guided imagery or progressive relaxation. Most want to overcome long-term personal challenges with weight, stress, addiction or fear.

Most clients are pursuing hypnotherapy for the first time. They are not only new to hypnosis but have no experience with meditation, guided imagery or progressive relaxation. Most want to overcome long-term personal challenges with weight, stress, addiction or fear.

In fact, most clients experience unexpected freedom, clarity and relief in areas unrelated to what they came to fix because of this meditative effect. In general, they are more relaxed and confident which usually translates into better communication with others and a sense of feeling more in control. Clients also typically report increased depth and quality sleep; awakening more refreshed and energized.

In fact, most clients experience unexpected freedom, clarity and relief in areas unrelated to what they came to fix because of this meditative effect. In general, they are more relaxed and confident which usually translates into better communication with others and a sense of feeling more in control. Clients also typically report increased depth and quality sleep; awakening more refreshed and energized.