Some argue that hypnosis is just a trick. Others, however, see it as bordering on the paranormal – mysteriously transforming people into mindless robots. Now our recent review of a number of research studies on the topic reveals it is actually neither. Hypnosis may just be an aspect of normal human behavior.

Some argue that hypnosis is just a trick. Others, however, see it as bordering on the paranormal – mysteriously transforming people into mindless robots. Now our recent review of a number of research studies on the topic reveals it is actually neither. Hypnosis may just be an aspect of normal human behavior.

Hypnosis refers to a set of procedures involving an induction – which could be fixating on an object, relaxing or actively imagining something – followed by one or more suggestions, such as “You will be completely unable to feel your left arm”.

The purpose of the induction is to induce a mental state in which participants are focused on instructions from the experimenter or therapist, and are not distracted by everyday concerns. One reason why hypnosis is of interest to scientists is that participants often report that their responses feel automatic or outside their control.

Most inductions produce equivalent effects. But inductions aren’t actually that important. Surprisingly, the success of hypnosis doesn’t rely on special abilities of the hypnotist either – although building rapport with them will certainly be valuable in a therapeutic context.

Rather, the main driver for successful hypnosis is one’s level of “hypnotic suggestibility”. This is a term which describes how responsive we are to suggestions. We know that hypnotic suggestibility doesn’t change over time and is heritable. Scientists have even found that people with certain gene variants are more suggestible.

Most people are moderately responsive to hypnosis. This means they can have vivid changes in behavior and experience in response  to hypnotic suggestions. By contrast, a small percentage (around 10-15%) of people are mostly non-responsive. But most research on hypnosis is focused on another small group (10-15%) who are highly responsive.

to hypnotic suggestions. By contrast, a small percentage (around 10-15%) of people are mostly non-responsive. But most research on hypnosis is focused on another small group (10-15%) who are highly responsive.

In this group, suggestions can be used to disrupt pain, or to produce hallucinations and amnesia. Considerable evidence from brain imaging reveals that these individuals are not just faking or imagining these responses.

Indeed, the brain acts differently when people respond to hypnotic suggestions than when they imagine or voluntarily produce the same responses. Preliminary research has shown that highly suggestible individuals may have unusual functioning and connectivity in the prefrontal cortex.

This is a brain region that plays a critical role in a range of psychological functions including planning and the monitoring of one’s mental states. There is also some evidence that highly suggestible individuals perform more poorly on cognitive tasks known to depend on the prefrontal cortex, such as working memory.

However, these results are complicated by the possibility that there might be different sub types of highly suggestible individuals. These neurocognitive differences may lend insights into how highly suggestible individuals respond to suggestions: they may be more responsive because they’re less aware of the intentions underlying their responses.

For example, when given a suggestion to not experience pain, they may suppress the pain but not be aware of their intention to do so. This may also explain why they often report that their experience occurred outside their control. Neuroimaging studies have not as yet verified this hypothesis but hypnosis does seem to involve changes in brain regions involved in monitoring of mental states, self-awareness and related functions.

For example, when given a suggestion to not experience pain, they may suppress the pain but not be aware of their intention to do so. This may also explain why they often report that their experience occurred outside their control. Neuroimaging studies have not as yet verified this hypothesis but hypnosis does seem to involve changes in brain regions involved in monitoring of mental states, self-awareness and related functions.

Although the effects of hypnosis may seem unbelievable, it’s now well accepted that beliefs and expectations can dramatically impact human perception. It’s actually quite similar to the placebo response, in which an ineffective drug or therapeutic treatment is beneficial purely because we believe it will work. In this light, perhaps hypnosis isn’t so bizarre after all. Seemingly sensational responses to hypnosis may just be striking instances of the powers of suggestion and beliefs to shape our perception and behavior. What we think will happen morphs seamlessly into what we ultimately experience.

Hypnosis requires the consent of the participant or patient. You cannot be hypnotized against your will and, despite popular misconceptions, there is no evidence that hypnosis could be used to make you commit immoral acts against your will.

Hypnosis as medical treatment

Meta-analyses, studies that integrate data from many studies on a specific topic, have shown that hypnosis works quite well when it comes to treating certain conditions. These include irritable bowel syndrome and chronic pain. But for other conditions, however, such as smoking, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder, the evidence is less clear cut – often because there is a lack of reliable research.

But although hypnosis can be valuable for certain conditions and symptoms, it’s not a panacea. Anyone considering seeking hypnotherapy should do so only in consultation with a trained professional. Unfortunately, in some countries, including the UK, anyone can legally present themselves as a hypnotherapist and start treating clients. However, anyone using hypnosis in a clinical or therapeutic context needs to have conventional training in a relevant discipline, such as clinical psychology, medicine, or dentistry to ensure that they are sufficiently expert in that specific area.

should do so only in consultation with a trained professional. Unfortunately, in some countries, including the UK, anyone can legally present themselves as a hypnotherapist and start treating clients. However, anyone using hypnosis in a clinical or therapeutic context needs to have conventional training in a relevant discipline, such as clinical psychology, medicine, or dentistry to ensure that they are sufficiently expert in that specific area.

We believe that hypnosis probably arises through a complex interaction of neurophysiological and psychological factors – some described here and others unknown. It also seems that these vary across individuals.

But as researchers gradually learn more, it has become clear that this captivating phenomenon has the potential to reveal unique insights into how the human mind works. This includes fundamental aspects of human nature, such as how our beliefs affect our perception of the world and how we come to experience control over our actions.

By: Devin Terhune and Steven Jay Lynn

By scanning the brains of subjects while they were hypnotized, researchers at the School of Medicine were able to see the neural changes associated with hypnosis.

By scanning the brains of subjects while they were hypnotized, researchers at the School of Medicine were able to see the neural changes associated with hypnosis.

Your eyelids are getting heavy, your arms are going limp and you feel like you’re floating through space. The power of hypnosis to alter your mind and body like this is all thanks to changes in a few specific areas of the brain, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered.

The scientists scanned the brains of 57 people during guided hypnosis sessions similar to those that might be used clinically to treat anxiety, pain or trauma. Distinct sections of the brain have altered activity and connectivity while someone is hypnotized, they report in a study published online July 28 in Cerebral Cortex.

“Now that we know which brain regions are involved, we may be able to use this knowledge to alter someone’s capacity to be hypnotized or the effectiveness of hypnosis for problems like pain control,” said the study’s senior author, David Spiegel, MD, professor and associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

A serious science

For some people, hypnosis is associated with loss of control or stage tricks. But doctors like Spiegel know it to be a serious science, revealing the brain’s ability to heal medical and psychiatric conditions.

“Hypnosis is the oldest Western form of psychotherapy, but it’s been tarred with the brush of dangling watches and purple capes,” said Spiegel, who holds the Jack, Samuel and Lulu Wilson Professorship in Medicine. “In fact, it’s a very powerful means of changing the way we use our minds to control perception and our bodies.”

Despite a growing appreciation of the clinical potential of hypnosis, though, little is known about how it works at a physiological level. While researchers have previously scanned the brains of people undergoing hypnosis, those studies have been designed to pinpoint the effects of hypnosis on pain, vision and other forms of perception, and not the state of hypnosis itself.

“There had not been any studies in which the goal was to simply ask what’s going on in the brain when you’re hypnotized,” said Spiegel.

Finding the most susceptible

Finding the most susceptible

To study hypnosis itself, researchers first had to find people who could or couldn’t be hypnotized. Only about 10 percent of the population is generally categorized as “highly hypnotizable,” while others are less able to enter the trancelike state of hypnosis.

Spiegel and his colleagues screened 545 healthy participants and found 36 people who consistently scored high on tests of hypnotizability, as well as 21 control subjects who scored on the extreme low end of the scales.

Then, they observed the brains of those 57 participants using functional magnetic resonance imaging, which measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow. Each person was scanned under four different conditions — while resting, while recalling a memory and during two different hypnosis sessions.

“It was important to have the people who aren’t able to be hypnotized as controls,” said Spiegel. “Otherwise, you might see things happening in the brains of those being hypnotized but you wouldn’t be sure whether it was associated with hypnosis or not.”

Brain activity and connectivity

Spiegel and his colleagues discovered three hallmarks of the brain under hypnosis. Each change was seen only in the highly hypnotizable group and only while they were undergoing hypnosis.

First, they saw a decrease in activity in an area called the dorsal anterior cingulate, part of the brain’s salience network. “In hypnosis, you’re so absorbed that you’re not worrying about anything else,” Spiegel explained.

Secondly, they saw an increase in connections between two other areas of the brain — the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula. He described this as a brain-body connection that helps the brain process and control what’s going on in the body.

Secondly, they saw an increase in connections between two other areas of the brain — the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula. He described this as a brain-body connection that helps the brain process and control what’s going on in the body.

Finally, Spiegel’s team also observed reduced connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the default mode network, which includes the medial prefrontal and the posterior cingulate cortex.

This decrease in functional connectivity likely represents a disconnect between someone’s actions and their awareness of their actions, Spiegel said. “When you’re really engaged in something, you don’t really think about doing it — you just do it,” he said.

During hypnosis, this kind of disassociation between action and reflection allows the person to engage in activities either suggested by a clinician or self-suggested without devoting mental resources to being self-conscious about the activity.

Treating pain and anxiety without pills

In patients who can be easily hypnotized, hypnosis sessions have been shown to be effective in lessening chronic pain, the pain of childbirth and other medical procedures; treating smoking addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder; and easing anxiety or phobias. The new findings about how hypnosis affects the brain might pave the way toward developing treatments for the rest of the population — those who aren’t naturally as susceptible to hypnosis.

“We’re certainly interested in the idea that you can change people’s ability to be hypnotized by stimulating specific areas of the brain,” said Spiegel.

A treatment that combines brain stimulation with hypnosis could improve the known analgesic effects of hypnosis and potentially replace addictive and side-effect-laden painkillers and anti-anxiety drugs, he said. More research, however, is needed before such a therapy could be implemented.

The study’s lead author is Heidi Jiang, a former research assistant at Stanford who is currently a graduate student in neuroscience at Northwestern University.

Other Stanford co-authors are clinical assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences Matthew White, MD; and associate professor of neurology Michael Greicius, MD, MPH.

The study was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (grant RCIAT0005733), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (grant P41EB015891), the Randolph H. Chase, M.D. Fund II, the Jay and Rose Phillips Family Foundation and the Nissan Research Center.

Stanford’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences also supported the work.

By; Sarah P. Williams

Hypnosis is synonymous with stage entertainment where the performer puts volunteers from the audience into a trance and commands them to do embarrassing things.

Hypnosis is synonymous with stage entertainment where the performer puts volunteers from the audience into a trance and commands them to do embarrassing things.

This makes it sound like a joke, but in fact hypnosis is a real phenomenon and it is proving increasingly useful to psychologists and neuroscientists, granting new insights into mental processes and medically unexplained neurological disorders.

That’s according to David Oakley and Peter Halligan who have written an authoritative new review, debunking hypnosis myths, and covering ways that neuroscience is shedding light on hypnosis and ways hypnosis is aiding neuroscience.

Despite popular folklore, hypnosis is not a form of sleep (this misconception isn’t helped by the fact that hypnosis studies typically label the control condition the “waking state”). However, Oakley and Halligan say new brain imaging findings do support the contention that hypnosis is a distinct form of consciousness.

After successful hypnotic induction, which involves using mental strategies to reach “a focused and absorbed attentional state”, participants show reduced activity in parts of the brain’s default mode network together with increased activity in prefrontal attentional systems. Oakley and Halligan concede that “it remains to be seen if these particular changes are unique to hypnosis.”

After hypnotic induction (or in some cases even without it) participants exposed to suggestive statements can experience altered perceptual or bodily sensations.

For instance, told that their arm is getting heavier and they cannot move it, a suggestible participant may experience paralysis of the arm. Sceptics may wonder  about the veracity of these experiences but brain imaging results are indicating they are real and not merely imagined.

about the veracity of these experiences but brain imaging results are indicating they are real and not merely imagined.

Consider a study of participants hypnotized and induced to see colorful Mondrian images in grey. Brain scan results of these participants showed altered activity in fusiform regions involved in color processing, and crucially such changes weren’t observed when the participants merely imagined the Mondrians in grey.

Another study showed that the famous Stroop effect disappeared when hypnotized participants received the suggestion that they would see words as meaningless symbols.

Another line of research explores the correlates of hypnotic suggestibility. Apparently, it is a highly stable trait and it is heritable.

It doesn’t correlate with the main personality dimensions but does correlate with creativity, empathy, mental absorption, fantasy proneness and people’s expectation that they will be prone to hypnotic procedures.

Many neurological symptoms are medically unexplained with no apparent organic cause and it is here that hypnosis is proving especially useful as a new way to model, explore and treat people’s symptoms.

Many neurological symptoms are medically unexplained with no apparent organic cause and it is here that hypnosis is proving especially useful as a new way to model, explore and treat people’s symptoms.

For instance people can be hypnotized to experience limb paralysis in a way that appears similar to the paralysis observed in conversion disorder.

People can also be hypnotically induced to experience the sense that there is a stranger looking back at them when they peer in a mirror – an apparent analogue of the real “mirrored-self-misidentification delusion”.

Hypnosis research is also exposing the apparent volitional element to mental phenomena previously considered automatic.

For example, a patient who experienced face-color synaesthesia received post-hypnotic suggestion that abolished the colors she usually sees with faces (as confirmed by a color-naming task in which faces no longer had an interfering effect).

“The psychological disposition to modify and generate experiences following targeted suggestion remains one of the most remarkable but under-researched human cognitive abilities given its striking causal influence on behavior and consciousness,” said Oakley and Halligan. (Oakley DA, and Halligan PW 2013)

90.6% Success Rate for Smoking Cessation: Of 43 consecutive patients undergoing this treatment protocol, 39 reported remaining abstinent from tobacco use at follow-up 6 months to 3 years post-treatment. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2001 Jul;49(3):257-66. Barber J.

Hypnosis 30 Times as Effective for Weight Loss: Investigated the effects of hypnosis in weight loss for 60 females, at least 20% overweight. Treatment included group hypnosis with metaphors for ego-strengthening, decision making and motivation, ideomotor exploration in individual hypnosis, and group hypnosis with maintenance suggestions. Hypnosis was more effective than a control group: an average of 17 lbs lost by the hypnosis group vs. an average of 0.5 lbs lost by the control group on follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 489-492.

Hypnosis Reduces Frequency and Intensity of Migraines: Results show that the number of attacks and the number of people who suffered blinding attacks were significantly lower for the group receiving hypnotherapy than for the group receiving medication. International Journal of Clinical & Experimental Hypnosis 1975; 23(1): 48-58.

Hypnosis Reduces Pain and Speeds up Recovery from Surgery: Since 1992, we have used hypnosis routinely in more than 1400 patients undergoing surgery. We found that hypnosis improved intraoperative patient comfort, reduced anxiety, pain, intraoperative requirements for anxiolytic and analgesic drugs, optimal surgical conditions and a faster recovery of the patient. Rev Med Liege. 1998 Jul; 53(7):414-8.

Hypnosis Lowered Post-treatment Pain in Burn Injuries: Patients in the hypnosis group reported less post treatment pain than did patients in the control group. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology 1997; 65(1): 60-7.

Healed 41% faster from fracture and surgery: Two studies from Harvard Medical School show hypnosis significantly reduces the time it takes to heal. Study One: Six weeks after an ankle fracture, those in the hypnosis group showed the equivalent of eight and a half weeks of healing. Study Two: Three groups of people studied after breast reduction surgery. Hypnosis group healed “significantly faster” than supportive attention group and control group. Harvard Medical School Gazette May 8, 2003

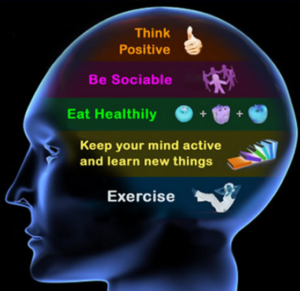

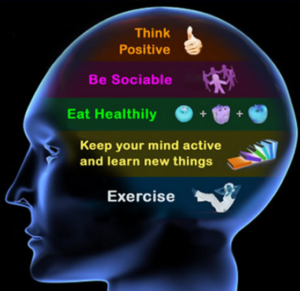

Sometimes it can be hard to look on the bright side of life — and those are the times when it might be most important to do so. A recent research paper published online in September 2013 in a journal of the American Heart Association shows that even for people dealing with heart disease — the number one killer of adults in this country — a positive outlook means living longer and stronger, or as we say, living younger.

The study, which looked at 607 patients in a hospital in Denmark, found that patients whose moods were overall more positive were 58 percent more likely to live at least another five years. These people exercised more, too.

The scientists can’t say for sure if positivity led to exercise or if exercise improved mood, but we say that the important message is the same either way: Positive thinking and regular physical activity are really important for life and beauty, too.

One of the reasons we love this study so much is that we’ve been saying this the whole time! Having the right attitude is even more important for your body than daily sunscreen and a weekend spa getaway, every other week — yes, that important.

Humor improves immune cell function, helps you ward off illness and decreases your chances of cancer — and apparently also increases your chance of living after heart disease hits. Not bad! We’d rather you change your exercise, food and stress management programs now so heart disease is unlikely in the first place.

And the chicken-or-egg thing doesn’t bother us at all. Physical activity improves mood, so if working out makes you feel better, that’s great. It does us. The other side of this two-headed coin is that feeling happier and more optimistic helps motivate you to engage in healthful habits. That might mean a hike in the woods, hopping on a treadmill, eating more vegetables or all of the above. It’s a win-win as we see it.

How to Get on the Positive Track

It’s not like you can go to your doctor and get a prescription for positivity. (What would it say, “Tell two jokes every 4 to 6 hours”?) You have to take the initiative to inject humor into your life. There are some obvious ways and some less obvious ways. First, the obvious ones.

TiVo Letterman and the Daily Show (because sleep is important for health, too), read a blog that makes you laugh, or hang out with friends who never fail to boost your mood, no matter how much of a sourpuss you’ve been.

Go to the park with your dog, play dress up with your kids; anything that’s going to bring a smile to your face is good medicine.

Some less obvious choices? Studies have shown that helping others helps you, too. Volunteering is a great way to give as much as you get and get as much as you give. Practice gratitude, which means thinking of, or writing down the things that you are grateful for in your life.

Positive affirmations remind you of the wonderful things in your life and make you feel happier and more satisfied.

It’s a positive cycle: The more you do it, the easier it gets — and the younger you’ll feel and look.

By: Dr. Oz and Dr. Roizen

Some argue that hypnosis is just a trick. Others, however, see it as bordering on the paranormal – mysteriously transforming people into mindless robots. Now our recent review of a number of research studies on the topic reveals it is actually neither. Hypnosis may just be an aspect of normal human behavior.

Some argue that hypnosis is just a trick. Others, however, see it as bordering on the paranormal – mysteriously transforming people into mindless robots. Now our recent review of a number of research studies on the topic reveals it is actually neither. Hypnosis may just be an aspect of normal human behavior. to hypnotic suggestions. By contrast, a small percentage (around 10-15%) of people are mostly non-responsive. But most research on hypnosis is focused on another small group (10-15%) who are highly responsive.

to hypnotic suggestions. By contrast, a small percentage (around 10-15%) of people are mostly non-responsive. But most research on hypnosis is focused on another small group (10-15%) who are highly responsive. For example, when given a suggestion to not experience pain, they may suppress the pain but not be aware of their intention to do so. This may also explain why they often report that their experience occurred outside their control. Neuroimaging studies have not as yet verified this hypothesis but hypnosis does seem to involve changes in brain regions involved in monitoring of mental states, self-awareness and related functions.

For example, when given a suggestion to not experience pain, they may suppress the pain but not be aware of their intention to do so. This may also explain why they often report that their experience occurred outside their control. Neuroimaging studies have not as yet verified this hypothesis but hypnosis does seem to involve changes in brain regions involved in monitoring of mental states, self-awareness and related functions. should do so only in consultation with a trained professional. Unfortunately, in some countries, including the UK, anyone can legally present themselves as a hypnotherapist and start treating clients. However, anyone using hypnosis in a clinical or therapeutic context needs to have conventional training in a relevant discipline, such as clinical psychology, medicine, or dentistry to ensure that they are sufficiently expert in that specific area.

should do so only in consultation with a trained professional. Unfortunately, in some countries, including the UK, anyone can legally present themselves as a hypnotherapist and start treating clients. However, anyone using hypnosis in a clinical or therapeutic context needs to have conventional training in a relevant discipline, such as clinical psychology, medicine, or dentistry to ensure that they are sufficiently expert in that specific area.

By scanning the brains of subjects while they were hypnotized, researchers at the School of Medicine were able to see the neural changes associated with hypnosis.

By scanning the brains of subjects while they were hypnotized, researchers at the School of Medicine were able to see the neural changes associated with hypnosis. Finding the most susceptible

Finding the most susceptible Secondly, they saw an increase in connections between two other areas of the brain — the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula. He described this as a brain-body connection that helps the brain process and control what’s going on in the body.

Secondly, they saw an increase in connections between two other areas of the brain — the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula. He described this as a brain-body connection that helps the brain process and control what’s going on in the body.

Hypnosis is synonymous with stage entertainment where the performer puts volunteers from the audience into a trance and commands them to do embarrassing things.

Hypnosis is synonymous with stage entertainment where the performer puts volunteers from the audience into a trance and commands them to do embarrassing things. about the veracity of these experiences but brain imaging results are indicating they are real and not merely imagined.

about the veracity of these experiences but brain imaging results are indicating they are real and not merely imagined. Many neurological symptoms are medically unexplained with no apparent organic cause and it is here that hypnosis is proving especially useful as a new way to model, explore and treat people’s symptoms.

Many neurological symptoms are medically unexplained with no apparent organic cause and it is here that hypnosis is proving especially useful as a new way to model, explore and treat people’s symptoms.