Difference between hypnotherapy and meditation

Hypnosis and meditation are both trance states that result in similar brain wave patterns. Hypnosis uses the guidance of a therapist, whereas meditation is usually done independently.

Hypnosis and meditation are both trance states that result in similar brain wave patterns. Hypnosis uses the guidance of a therapist, whereas meditation is usually done independently.

Hypnosis is a trance-like state of heightened awareness. Everyone goes in and out of natural trances many times a day.

If you’ve ever walked or driven somewhere while concentrating so deeply on something else that when you arrived, you couldn’t remember the actual process of driving or walking, then you’ll know what it is to be in a trance. Hypnosis is such a state brought about with the aid of a hypnotist or hypnotherapist.

Hypnotherapy is therapy conducted whilst the client is under Hypnosis. Hypnotherapy works by inducing a trance-like state within a client during which they are relaxed but fully aware of their surroundings and only concentrating on the hypnotherapist’s voice. It is different from sleep and closer to a relaxed state of wakefulness where breathing and heart-rate slows and brain-waves change.

The client is alert, always exercises choice and control, and is empowered by accessing their own inner resources and healing ability rather than simply obeying a command. Once in a state of hypnosis, under the guidance of the hypnotherapist, the client is able to take control over any involuntary thoughts, behavior or feelings taking place in the sub-conscious, thereby bringing about the changes they want, such as reducing unwanted behaviors or making changes they find hard to make.

As with all things, some people will enter a hypnotic trance more easily than others. But because trance is a natural state, anyone can be hypnotized providing a)  they understand what is spoken to them, and b) they consent to the process.

they understand what is spoken to them, and b) they consent to the process.

If you feel uncertain or insecure you should spend time with your hypnotherapist first to establish trust and rapport. This will make the process smoother and more comfortable and increase the likelihood of successful therapy.

Although the hypnotherapist is offering suggestions to the unconscious mind, the client will not accept a suggestion that they choose not to.

In hypnotherapy, the client is not under the control of the hypnotherapist. Hypnosis is not something imposed on people, but something they do for themselves. A hypnotherapist simply serves as a facilitator to guide them.

Hypnotherapy is most effective when the client is highly motivated. This is why it is so important that you come to therapy because YOU want to, and not because someone else wants you to.

As with any therapeutic modality some clients will experience great benefits and other less. But there is now ample scientific evidence that Hypnotherapy can be highly effective in treating many conditions ranging from chronic pain and depression to weight loss.

Meditation is also a state of heightened focus or awareness. It is a practice during which the mind’s mental activity may be slowed, and deep mental and physical relaxation may occur. The practice is simple but not easy. As with any newly learned skill, patience and persistence are necessary for lasting benefit.

Meditation taps into the innate potential for healing that we all have. It mobilizes and develops our ability for self-awareness and self-compassion as well as compassion for others, helping to improve self-esteem and providing a general feeling of relaxed well-being.

Mindfulness is the capacity to be completely present and attentive. A common definition used is “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally”.

Meditation is the formal practice that trains the brain to be focused and present. Meditation has been shown to help manage pain and anxiety, lessen mind-chatter and enhance the natural healing process of the body and mind.

Mindfulness is the moment to moment practice through the day that helps to maintain awareness of being present with all that occurs, good or bad, without judgement. This awareness is empowering and allows one to slow down and live one’s life fully, not just watch it speeding by.

Mindfulness is the moment to moment practice through the day that helps to maintain awareness of being present with all that occurs, good or bad, without judgement. This awareness is empowering and allows one to slow down and live one’s life fully, not just watch it speeding by.

By practicing non-judgment, we can learn to savor what is good in our lives and be more accepting of what isn’t. After all, judgment of a situation doesn’t change what it is. Mindfulness can open us up to the possibilities that exist in each moment of our lives, to experience the fullness and uniqueness of each moment. Practiced regularly, mindfulness can help us to work more productively and live more harmoniously.

By: Judith Lissing

Study IDs brain altered during hypnosis

By scanning the brains of subjects while they were hypnotized, researchers at the School of Medicine were able to see the neural changes associated with hypnosis. Stanford researchers found changes in three areas of the brain that occur when people are hypnotized.

By scanning the brains of subjects while they were hypnotized, researchers at the School of Medicine were able to see the neural changes associated with hypnosis. Stanford researchers found changes in three areas of the brain that occur when people are hypnotized.

Your eyelids are getting heavy, your arms are going limp and you feel like you’re floating through space. The power of hypnosis to alter your mind and body like this is all thanks to changes in a few specific areas of the brain, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered.

The scientists scanned the brains of 57 people during guided hypnosis sessions similar to those that might be used clinically to treat anxiety, pain or trauma. Distinct sections of the brain have altered activity and connectivity while someone is hypnotized, they report in a study published online July 28 in Cerebral Cortex.

“Now that we know which brain regions are involved, we may be able to use this knowledge to alter someone’s capacity to be hypnotized or the effectiveness of hypnosis for problems like pain control,” said the study’s senior author, David Spiegel, MD, professor and associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

A serious science

For some people, hypnosis is associated with loss of control or stage tricks. But doctors like Spiegel know it to be a serious science, revealing the brain’s ability to heal medical and psychiatric conditions.

“Hypnosis is the oldest Western form of psychotherapy, but it’s been tarred with the brush of dangling watches and purple capes,” said  Spiegel, who holds the Jack, Samuel and Lulu Willson Professorship in Medicine. “In fact, it’s a very powerful means of changing the way we use our minds to control perception and our bodies.”

Spiegel, who holds the Jack, Samuel and Lulu Willson Professorship in Medicine. “In fact, it’s a very powerful means of changing the way we use our minds to control perception and our bodies.”

Despite a growing appreciation of the clinical potential of hypnosis, though, little is known about how it works at a physiological level.

Secondly, they saw an increase in connections between two other areas of the brain — the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula. He described this as a brain-body connection that helps the brain process and control what’s going on in the body.

Finally, Spiegel’s team also observed reduced connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the default mode network, which includes the medial prefrontal and the posterior cingulate cortex.

This decrease in functional connectivity likely represents a disconnect between someone’s actions and their awareness of their actions, Spiegel said. “When you’re really engaged in something, you don’t really think about doing it — you just do it,” he said.

During hypnosis, this kind of disassociation between action and reflection allows the person to engage in activities either suggested by a clinician or self-suggested without devoting mental resources to being self-conscious about the activity.

Brain activity and connectivity

Spiegel and his colleagues discovered three hallmarks of the brain under hypnosis. Each change was seen only in the highly hypnotizable group and only while they were undergoing hypnosis.

First, they saw a decrease in activity in an area called the dorsal anterior cingulate, part of the brain’s salience network. “In hypnosis, you’re so absorbed that you’re not worrying about anything else,” Spiegel explained. It’s a very powerful means of changing the way we use our minds to control perception and our bodies.

First, they saw a decrease in activity in an area called the dorsal anterior cingulate, part of the brain’s salience network. “In hypnosis, you’re so absorbed that you’re not worrying about anything else,” Spiegel explained. It’s a very powerful means of changing the way we use our minds to control perception and our bodies.

Secondly, they saw an increase in connections between two other areas of the brain — the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula. He described this as a brain-body connection that helps the brain process and control what’s going on in the body.

Finally, Spiegel’s team also observed reduced connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the default mode network, which includes the medial prefrontal and the posterior cingulate cortex.

This decrease in functional connectivity likely represents a disconnect between someone’s actions and their awareness of their actions, Spiegel said. “When you’re really engaged in something, you don’t really think about doing it — you just do it,” he said.

During hypnosis, this kind of disassociation between action and reflection allows the person to engage in activities either suggested by a clinician or self-suggested without devoting mental resources to being self-conscious about the activity.

Treating pain and anxiety without pills

In patients who can be easily hypnotized, hypnosis sessions have been shown to be effective in lessening chronic pain, the pain of childbirth and other medical procedures; treating smoking addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder; and easing anxiety or phobias.

The new findings about how hypnosis affects the brain might pave the way toward developing treatments for the rest of the population, those who aren’t naturally as susceptible to hypnosis. “We’re certainly interested in the idea that you can change people’s ability to be hypnotized by stimulating specific areas of the brain,” said Spiegel.

who aren’t naturally as susceptible to hypnosis. “We’re certainly interested in the idea that you can change people’s ability to be hypnotized by stimulating specific areas of the brain,” said Spiegel.

A treatment that combines brain stimulation with hypnosis could improve the known analgesic effects of hypnosis and potentially replace addictive and side-effect-laden painkillers and anti-anxiety drugs, he said. More research, however, is needed before such a therapy could be implemented.

By: Sarah C.P. Williams

Can hypnotherapy treat anxiety

Anxiety disorders affect 40 million Americans each year, which makes anxiety the most common mental illness in the United States.

Anxiety disorders affect 40 million Americans each year, which makes anxiety the most common mental illness in the United States.

There are many well-known forms of treatment for anxiety disorders including:

- cognitive behavioral therapy

- exposure therapy

- medication

But some people choose to treat their anxiety with alternative treatments like hypnotherapy.

What is hypnotherapy?

Contrary to what you’ve seen in movies, hypnosis involves a lot more than traveling into a trance-like state after looking into someone’s eyes.

During a hypnosis session, you undergo a process that helps you relax and focus your mind. This state is similar to sleep, but your mind will be very focused and more able to respond to suggestion.

While in this relaxed state, it’s believed that you’re more willing to focus on your subconscious mind. This allows you to explore some of the deeper issues you’re dealing with.

Hypnotherapy sessions may be used to:

Hypnotherapy sessions may be used to:

- explore repressed memories, such as abuse

- instill a desire for healthy habits that can lead to weight loss

- help to relax and reprogram an anxious brain

The practitioner, or therapist, is there to help guide this process. They aren’t there to control your mind.

What are the benefits of using hypnotherapy to treat anxiety?

Even though hypnotherapy isn’t as widely known as psychotherapy and medication for treating anxiety, researchers and scientists have been studying the effects it can have on mental health conditions such as anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depression for several years.

In one 2016 study, researchers scanned the brains of people while they were undergoing guided hypnosis sessions. They found that a hypnotized brain experiences changes in the brain that give a person:

- focused attention

- greater physical and emotional control

- less self-consciousness

How is hypnotherapy used to treat anxiety?

Let’s say you have a fear of flying. During a hypnotherapy session, the therapist can give you what’s known as a “posthypnotic suggestion” while you’re in a state of trance.

In this dreamlike state, the mind becomes more open to suggestion. This allows the therapist to suggest to you how easily confident you will be the next time you sit on a plane.

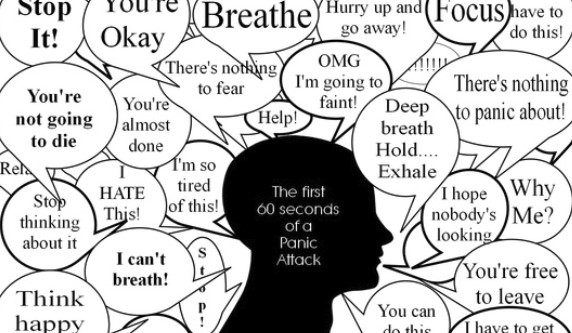

Because of the relaxed state you’re in, it can be easier to avoid escalating any anxiety symptoms you may feel, such as:

- a feeling of impending doom

- shortness of breath

- increased heart rate

- muscle tension

- irritability

- nervous stomach

Hypnotherapy should be used as a complementary treatment to cognitive behavioral therapy.

Hypnotherapy should be used as a complementary treatment to cognitive behavioral therapy.

However, if you only use hypnosis to treat your anxiety, it could have effects similar to those of meditation. A hypnotic induction would help put you into this relaxed state, just like meditation. You can then use this state to address anxieties and phobias.

So, if you’re trying to treat a fear of flying, you can visualize yourself going back to the first time you were scared of flying. You can use a technique called hypnoprojectives, where you visualize your past events as you would’ve liked to have seen them. Then you see yourself in the future, feeling calm and peaceful while on a plane.

What you need to know before trying hypnotherapy

As long as you’re seeing a licensed mental health professional who has extensive training in hypnosis, the use of hypnotherapy to treat anxiety is considered very safe.

The first thing to consider when choosing a hypnotist is the practitioner’s qualifications. Look for a licensed mental health care professional — such as a psychologist, psychotherapist, psychiatric nurse practitioner, counselor, social worker, or medical doctor — who is also a hypnotherapist.

An effective overall treatment plan should include several modalities (approaches), and hypnotherapy is just one of the many clinically effective tools known to help treat anxiety.

You can also ask if they’re affiliated with any professional associations, such as the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis.

If for example, a hypnotist uncovers trauma while doing hypnotherapy, they need to know how to treat trauma. In other words, having the education and training to diagnose and treat mental health conditions — which comes from being licensed — is a key component in the success of hypnotherapy.

Healthline.com

How hypnosis is used in psychology

What exactly is hypnosis?

What exactly is hypnosis?

While definitions can vary, the American Psychological Association describes hypnosis as a cooperative interaction in which the participant responds to the suggestions of the hypnotist.

Hypnosis has become well-known thanks to popular acts where people are prompted to perform unusual or ridiculous actions, but, it has also been clinically proven to provide medical and therapeutic benefits, most notably in the reduction of pain and anxiety. It has even been suggested that hypnosis can reduce the symptoms of dementia.

How Does Hypnosis Work?

When you hear the word hypnotist, what comes to mind? If you’re like many people, the word may conjure up images of a sinister stage-villain who brings about a hypnotic state by swinging a pocket watch back and forth.

In reality, hypnosis bears little resemblance to these stereotypical depictions. According to psychologist John Kihlstrom, “The hypnotist does not hypnotize the individual. Rather, the hypnotist serves as a sort of coach or tutor whose job is to help the person become hypnotized.”

While hypnosis is often described as a sleep-like trance state, it is better expressed as a state characterized by focused attention, heightened suggestibility, and vivid fantasies. People in a hypnotic state often seem sleepy and zoned out, but in reality, they are in a state of hyper-awareness.

In psychology, hypnosis is sometimes referred to as hypnotherapy and has been used for a number of purposes including the reduction and treatment of pain. Hypnosis is usually performed by a trained therapist who utilizes visualization and verbal repetition to induce a hypnotic state.

What Effects Does Hypnosis Have?

The experience of hypnosis can vary dramatically from one person to another. Some hypnotized individuals report feeling a sense of detachment or extreme relaxation during the hypnotic state while others even feel that their actions seem to occur outside of their conscious volition. Other individuals may remain fully aware and able to carry out conversations while under hypnosis.

Experiments by researcher Ernest Hilgard demonstrated how hypnosis can be used to dramatically alter perceptions. After instructing a hypnotized individual not to feel pain in his or her arm, the participant’s arm was then placed in ice water. While non-hypnotized individuals had to remove their arm from the water after a few seconds due to the pain, the hypnotized individuals were able to leave their arms in the icy water for several minutes without experiencing pain.

Symptoms or Conditions Hypnosis Is Commonly Used For

• The treatment of chronic pain conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis

• The treatment and reduction of pain during childbirth

• The reduction of the symptoms of dementia

• Hypnotherapy may be helpful for certain symptoms of ADHD

• The reduction of nausea and vomiting in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy

• Control of pain during dental procedures

• Elimination or reduction of skin conditions including warts and psoriasis

• Alleviation of symptoms associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

So why might a person decide to try hypnosis? In some cases, people might seek out hypnosis to help deal with chronic pain or to alleviate pain and anxiety caused by medical procedures such as surgery or childbirth. Hypnosis has also been used to help people with behavior changes such as quitting smoking, losing weight, or preventing bed-wetting.

Can You Be Hypnotized?

Can You Be Hypnotized?

While many people think tat they cannot be hypnotized, research has shown that a large number of people are more hypnotizable than they believe.

• Fifteen percent of people are very responsive to hypnosis.

• Children tend to be more susceptible to hypnosis.

• Approximately ten percent of adults are considered difficult or impossible to hypnotize.

• People who can become easily absorbed in fantasies are much more responsive to hypnosis.

If you are interested in being hypnotized, it is important to remember to approach the experience with an open mind. Research has suggested that individuals who view hypnosis in a positive light tend to respond better.

Theories of Hypnosis

One of the best-known theories is Hilgard’s neo-dissociation theory of hypnosis. According to Hilgard, people in a hypnotic state experience a split consciousness in which there are two different streams of mental activity.

While one stream of consciousness responds to the hypnotist’s suggestions, another dissociated stream processes information outside of the hypnotized individual’s conscious awareness.

Hypnosis Myths

Myth 1: When you wake up from hypnosis, you won’t remember anything that happened when you were hypnotized: While amnesia may occur in very rare cases, people generally remember everything that transpired while they were hypnotized. However, hypnosis can have a significant effect on memory. Posthypnotic amnesia can lead an individual to forget certain things that occurred before or during hypnosis. However, this effect is generally limited and temporary.

Myth 2: Hypnosis can help people remember the exact details of a crime: While hypnosis can be used to enhance memory, the effects have been dramatically exaggerated in popular media. Research has found that hypnosis does not lead to significant memory enhancement or accuracy, and hypnosis can actually result in false or distorted memories.

Myth 3: You can be hypnotized against your will: Despite stories about people being hypnotized without their consent, hypnosis requires voluntary participation on the part of the patient.

Myth 4: The hypnotist has complete control of your actions while you’re under hypnosis: While people often feel that their actions under hypnosis seem to occur without the influence of their will, a hypnotist cannot make you perform actions that are against your wishes.

Myth 5: Hypnosis can make you super-strong, fast or athletically talented: While hypnosis can be used to enhance performance, it cannot make people stronger or more athletic than their existing physical capabilities.

By Kendra Cherry

Hypnosis: grounded in science

Last summer, at age 14, Sue Jones suffered from stabbing pains in her abdomen that got so intense, “I couldn’t walk.”

Last summer, at age 14, Sue Jones suffered from stabbing pains in her abdomen that got so intense, “I couldn’t walk.”

She spent three weeks in a wheelchair while doctors ruled out everything from digestive problems to appendicitis. Finally, after a four-night stay at BC Children’s Hospital in Vancouver, she got a diagnosis: acute anxiety.

An honor student, Sue is thin, dark-haired and lily pale. (Her parents requested a pseudonym to protect her privacy.) When a doctor recommended hypnosis, she balked at first. “I thought of it as black magic, like witchcraft,” she says. But neither breathing exercises, nor anti-depressants, had taken away the pain.

So, in early September, she visited Dr. Leora Kuttner, a pediatric psychologist who specializes in clinical hypnosis, a technique for leveraging the brain’s healing abilities during a trance state.

Kuttner’s office has a rumpus-room feel, with toys, plants and colorful pictures scattered about. Settling into a plump beige armchair by the window, Sue breathed slowly as the psychologist asked her to “go to a quiet place.” She chose a beach. Then, in a soft, soothing voice, Kuttner suggested that she imagine a “protection skirt” that could shield her from stomach pain.

Sue pictured herself covered in “a golden, shimmery, transparent cocoon, floating up in the air above this beach.” For a few moments, she felt as though she had left the room. When Kuttner called her out of her reverie, “I was surprised where I was.” Another surprise: the pain was gone.

Sue keeps a recording of her “protection skirt” hypnosis handy on her phone – all 5 minutes, 56 seconds of it. She is still learning to keep anxiety at bay, but if the abdominal pain ever comes back, she says, “I know how to deal with it.”

Hypnosis isn’t just for hucksters and Hollywood villains any more. Neuroscience studies have shown that this mind-body therapy affects the brain in extraordinary ways. Clinical trials have demonstrated its effectiveness in treating anxiety, phobias, skin rashes, irritable-bowel syndrome and acute and chronic pain.

In France and Belgium, anesthesiologists are offering hypnosis combined with local anesthetic as an alternative to general anesthesia in surgery. In North America, medical centers such as the Mayo Clinic have added hypnosis to their pain-management tools.

Hypnosis doesn’t work for everyone, notes Dr. Amir Raz, Canada Research Chair in the cognitive neuroscience of attention at McGill University and the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal. But “in my opinion, it’s completely underused.”

That may be changing, especially in pediatrics. Over the past four years, Kuttner has been invited to teach hypnosis at the Mayo Clinic, Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary and the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Kuttner, who developed her techniques more than three decades ago, says she’s “thrilled” by the uptake.

As with mindfulness meditation, hypnosis harnesses the brain’s natural abilities to regulate the body and control the random thoughts that ricochet through our minds, says Dr. David Patterson, a University of Washington psychologist who has studied hypnosis since the 1980s, in a series of clinical trials financed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

But, he adds, meditation can take weeks or months of practice before it helps patients dial down pain. With hypnosis, “the relief is just a lot quicker and more dramatic.”

Hypnosis reduces our awareness of what’s going on around us, even as it increases our attention and openness to new ideas. The brain’s  command center lets its guard down, allowing the therapist’s suggestions to embed themselves into the parts of our grey matter that regulate our thoughts, perceptions and physiology, Patterson says. “It’s as if you’re talking directly to the brain.”

command center lets its guard down, allowing the therapist’s suggestions to embed themselves into the parts of our grey matter that regulate our thoughts, perceptions and physiology, Patterson says. “It’s as if you’re talking directly to the brain.”

At Legacy Oregon Burn Center in Portland, Ore., Dr. Emily Ogden, a psychologist, uses hypnosis to help patients cope with the most excruciating injuries you can have.

In the facility’s bedroom-sized intensive-care units, machinery for monitoring vital signs beeps nonstop as nurses and doctors cut away layers of clothing and scorched flesh. The air is putrid-sweet, the smell of open wounds.

Often, the pain of the burn itself pales next to the agony of having dead tissue removed in a process called debridement, or a patch of healthy skin shaved and grafted onto a wound. Then there are the dressing changes. Every day or so, nurses replace fluid-soaked gauze to prevent a burn victim’s greatest threat: infection. The sudden gust of cold air on exposed wounds can be torturous, even with painkillers.

Burn patients tend to be open to hypnosis, Ogden says, but they often add something such as, “I’m not going to squawk like a chicken, am I?”

After reassuring them that no, she won’t make them cluck, Ogden stands by the bedside and asks the patient to imagine stepping down a flight of stairs as she counts backward from 20. Once the patient is deeply relaxed, she gives a series of hypnotic “suggestions,” or instructions for the brain.

For example, “When a nurse touches you on the shoulder, you will return to the feeling of relaxation you have now,” she might say. “During the procedure, you will have no feelings other than comfort and relaxation. Later, you’ll be surprised at how easily it goes for you.”

As simple as it sounds, the technique usually works, says Ogden, who began offering hypnosis six months ago. “It has proven to be such a beneficial and effective intervention.”

Hypnosis stimulates specific brain activity, according to a 2016 study from Stanford University. Researchers found three brain changes in adults who scored high in susceptibility to hypnosis and these changes occurred only while they were hypnotized.

Using a brain-imaging technique called fMRI, researchers found decreased activity in the brain’s salience network, the inner “air-traffic controller” that processes stimuli and preps us for action.

Secondly, they saw greater connectivity between the brain’s executive-control network and the insula, a grape-sized region deeper in the brain that helps us “control what’s going on in the body, and process pain,” the study’s co-author, psychiatrist Dr. David Spiegel, says.

Finally, the researchers observed reduced connections between the executive-control center and the “default-mode” network, involved in self-reflection. This could lead to a disconnect between a person’s actions and their awareness of their actions, Spiegel says.

He describes hypnosis as a “very powerful means of changing the way we use our minds to control perception, and our bodies.” If more practitioners had training to use it, hypnosis could make “a huge difference” in the opioid epidemic, he adds.

In a previous study, published in The Lancet, Spiegel and colleagues instructed patients in self-hypnosis techniques before they underwent vascular or kidney procedures.

Compared with patients receiving standard care, the hypnosis group used significantly less pain medication (fentanyl and midazolam). Spiegel’s team is now testing the same approach in knee- and hip-surgery patients.

He notes that the risk of addiction increases when people are on opioid painkillers for more than three days. If patients can get through the post-surgical period faster, “you can prevent them from getting hooked.”

But hypnosis has an image problem. Unlike mindfulness, it lacks Zen-master cachet. Doctors and patients have trouble forgetting the dangling pocket watches of stage hypnosis, or the bad guys who put sleeper agents under “mind control” in movies such as The Manchurian Candidate.

But hypnosis has an image problem. Unlike mindfulness, it lacks Zen-master cachet. Doctors and patients have trouble forgetting the dangling pocket watches of stage hypnosis, or the bad guys who put sleeper agents under “mind control” in movies such as The Manchurian Candidate.

Despite solid evidence from clinical trials, the medical field’s approach to hypnosis has been “extremely careful and conservative,” Raz says.

And let’s face it: For every credible scientist studying hypnosis, there are hundreds of charlatans touting self-hypnosis CDs or sessions on Skype as a miracle cure for everything from obesity to cancer. In the land of psychics and crystal magic, anyone can become a “certified hypnotherapist” in a month or less. Rampant quackery “gives us a bad name,” Patterson says.

Adults tend to insist they are impervious to hypnosis, even if they’ve never tried it, Raz says. They think of it as “feeble-mindedness, or the ability to be manipulated.”

But in fact, people who respond to hypnosis may have better co-ordination between brain areas that “integrate attention, emotion, action and intention,” according to a 2012 study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry.

About 10 to 15 percent of adults are “highly hypnotizable,” meaning they can easily slip into a trance and act on hypnotic suggestions. The same percentage of adults do not respond to hypnosis at all, while the rest are somewhere in between. The trait may be genetic, researchers say. But imagination also plays a role.

Responsiveness to hypnosis reaches its peak between the ages of 8 and 12, says Kuttner, who began using hypnosis in the mid-1980s to help children cope with pain in the oncology ward at BC Children’s Hospital.

She documented her techniques in No Tears, No Fears, a short film featuring eight kids with cancer, aged 3 to 12. Guided by Kuttner, the children went through procedures such as spinal taps with only local anesthetic at the needle site. (At the time, general anesthesia in children was reserved for special circumstances, such as major surgery.)

Most children can easily imagine an invisible “magic glove” that keeps needles from hurting, or a fantasy world free of pain, Kuttner says. Concentrating on these beliefs can have analgesic effects. With a fond smile, she recalls a child with leukemia who spent her treatments in an imaginary land of candy.

A more recent patient, 17-year-old Isabella Hay, says working with Kuttner helped her overcome muscle twitches and symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Starting at the age of 4, Isabella learned to visualize entering a room and turning off switches that controlled her nervous ticks.

When Isabella received a diagnosis of OCD at the age of 13, Kuttner taught her how to focus on her breathing and picture herself in calm place, using a form of self-hypnosis. The technique has given her control over compulsive behaviors, such as a need to touch a rock a certain number of times, Isabella says.

She used to feel panicky at the idea of sleeping away from home. Now, she is graduating from high school with acceptance letters from both the University of British Columbia and Queen’s University. Knowing that the brain is strong enough to “transport you from the thoughts,” Isabella says, “I feel more secure and confident, and less vulnerable in my own head.”

Hypnosis techniques are relatively easy for health-care professionals to learn, Kuttner says. But like other specialists interviewed for this article, she cautions patients against seeking hypnosis from someone with no medical training. “Things can go haywire.”

A lay hypnotist could fail to recognize the signs of psychosis, or encourage someone to regress to an earlier life stage filled with traumatic memories, “and they won’t have a clue how to help the person.”

Kuttner recalls treating a patient who had gone to a lay hypnotist for headache relief but came away weeping and confused. Hypnosis needs to be in the hands of “someone who respects it, and knows what they are doing,” she says. “This is powerful stuff.”

In hypnosis circles, the word “powerful” comes up a lot. But it’s hardly an overstatement when you consider the work of Dr. Marie-Elisabeth Faymonville, director of the pain clinic and palliative care at the University Hospital of Liège, Belgium.

Hypnosis allows patients to avoid general anesthesia in surgeries ranging from mastectomies to heart-valve replacements, Faymonville says.

Since 1992, she has treated more than 9,500 surgery patients with “hypno-sedation,” combining hypnosis with small amounts of local  anesthesia. Of those patients, just 18 had to switch to general anesthesia. “It’s really rare,” she says, in German-accented English.

anesthesia. Of those patients, just 18 had to switch to general anesthesia. “It’s really rare,” she says, in German-accented English.

The method appeals to patients who want to be “aware during surgery, but comfortable.” Patients do not get a dry run. Instead, Faymonville assesses their level of motivation and confidence in the surgical team, and their ability to co-operate.

Hypno-sedation works because the patient wants it to work, she says: It’s the opposite of “mind control.” The anesthesiologist’s job is to use hypnotic techniques and communicate with the patient, but the patient must collaborate, “so he puts himself in the hypnotic state.”

She emphasizes that unlike the cross-section of patients you might find in the average hospital, her patients are “highly motivated” to stay conscious during surgery. But in general, she adds, doctors tend to underestimate the resources patients can access with their own minds. “Hypnosis is a talent, a gift from nature.”

THE GIFT OF HYPNOSIS

The ability to be hypnotized is a talent, like an ear for music, researchers say. The easiest way to know if you have it is to give it a try. So, I ask Dr. Lance Rucker, president of the Canadian Society of Clinical Hypnosis, if he’ll hypnotize me.

A dentist by training, Rucker teaches hypnosis to third-year dentistry students at the University of British Columbia, where it’s part of the required curriculum.

Dentists need to learn the basics of hypnosis to “avoid abusing the trance state,” he says. People drift in and out of light trances throughout the day, whether they’re on “autopilot” for the daily commute, or so engrossed in an X-Men flick that they forget it’s a movie.

Dental patients – triggered by memories of needles, drills and frozen-gums past – are often in a daze even before they lie on the chair. When patients are in this vulnerable state, a dentist’s soothing words (“let’s make sure you’re comfortable”) can help make it so. On the flip side, stock phrases such as, “this might hurt a little,” may intensify pain and fear, he says.

Rucker emphasizes that reputable practitioners will not use hypnosis for purposes outside their medical specialty. He asks if I have a dental issue I’d like to resolve. An overactive gag reflex, perhaps? Or a fear of dental fillings?

I am definitely a grinder. That may not be easily fixed, depending on the root cause, he replies. But he’s willing to give it a go.

We sit in the front seats of his scarlet Acura, parked outside a cluster of big-box stores near his home in Burnaby, B.C. The windows are closed to shut out the rumble of traffic and the air is warm and stuffy. I am drowsy already.

In a soft, calm voice, Rucker asks me to take myself to “an internal space, a creative space.” As I relax, he says, my inner awareness can let me know “what it’s all about, and has been all about – the clenching, the grinding.”

A symbol or realization may come to mind. He pauses for a few moments. Then he suggests that I ask my inner self whether it can let the grinding go, “or whether there is some part of you that may wish to hold on to it.”

As his voice meanders, I have a clear picture of a big black dog with massive metal jaws. Could my clenching be a hard-wired defense mechanism? It’s an obvious symbol. But as it turns out, my inner guard dog refuses to back down easily. Later that day, my jaw feels as tight as ever.

A life-long grinding habit could be a problem that a single session in a parked car cannot solve. I might give hypnosis another try. But maybe I just don’t have the gift.

By: Adrianna Barton